Alzheimer’s and Dementia: The Loss of Self and Voice

Will Ferrell caused a minor furor in April this year when it was announced that he would star in Reagan, a fictional comedy hinging on Ronald Reagan’s real-life battle with Alzheimer’s disease. In it, a confused and disorientated Reagan is still in presidency and has to be bluffed and cajoled into putting up a show of mental soundness by a quick-thinking intern, who is the only one aware of the president’s state of mind. Many expressed disappointment and disgust at the possibility of the movie, including Reagan’s children, Patti Davis and Michael Reagan, the former whom shared a glimpse into Reagan’s condition during his notoriously private later years with the disease.

“I watched as fear invaded my father’s eyes—this man who was never afraid of anything. I heard his voice tremble as he stood in the living room and said, ‘I don’t know where I am.’”

The brief recount offers insight into the pain and struggle experienced by the dementia-afflicted individual and their loved ones, and the upsetting scene of disorientation and fear is one that is hardly funny. Ferrell did eventually announce that he had no intention of filling the role, though the incident does bring into question a larger, more pressing issue that is the treatment and view of dementia sufferers, by normal, healthy society.

Among the many comments and stories made accusing Ferrell of insensitivity and thoughtlessness, were frequent mentions of personal experiences with the syndrome, recounting the anguish of lives that have been changed and scarred by dementia. Over 45 million people around the world live with some form of dementia, which has four principle types: Vascular, Frontotemporal, Lewy Body and Alzheimer’s, the last of which accounts for two-thirds of dementia cases alone. In 2015, the cost of dementia amounted to SGD 14 billion, and the world economy, USD 818 billion.

With a globally aging population and longer life expectancies, dementia cases (more common among persons aged 65 years and older), are expected to double every 20 years, reaching a figure of 131.5 million sufferers by 2050. The lack of cure or effective treatment, high costs and increasing prevalence of dementia make it not just a critical healthcare issue, but a hugely important social one as well.

Just as some balked at Reagan’s debilitating condition being taken for laughs, Meryl Streep’s depiction of an elderly, dementia-ridden Margaret Thatcher in The Iron Lady (2011) came under fire when the movie was released. Thatcher herself was then still alive, though incapacitated by what is widely presumed to be Alzheimer’s disease, unable to permit or control her portrayal. Others, including medical professionals protested, resenting the pronounced and pathetic scenes of a helpless and defenseless Thatcher in her sunset years as exploitative and invasive voyeurism.

As heartrending as Streep’s portrayal of an elderly Thatcher was, the fact remained that the once fiery and assertive woman was still just then suffering from the debilitating condition, making what would have been an emphatic and thoughtful performance, one of speculative and grotesque pantomime instead.

Both the cases of Thatcher and Reagan raise questions about whether dementia sufferers, especially those in the advanced stages of the disease, are still recognised as valid participants and rightful members of society, or regarded as socially-dead, invalid figures. While there were expressions of concern and dismay in both incidences, they did not raise sufficient public interest enough to rally serious, widespread debate and consideration.

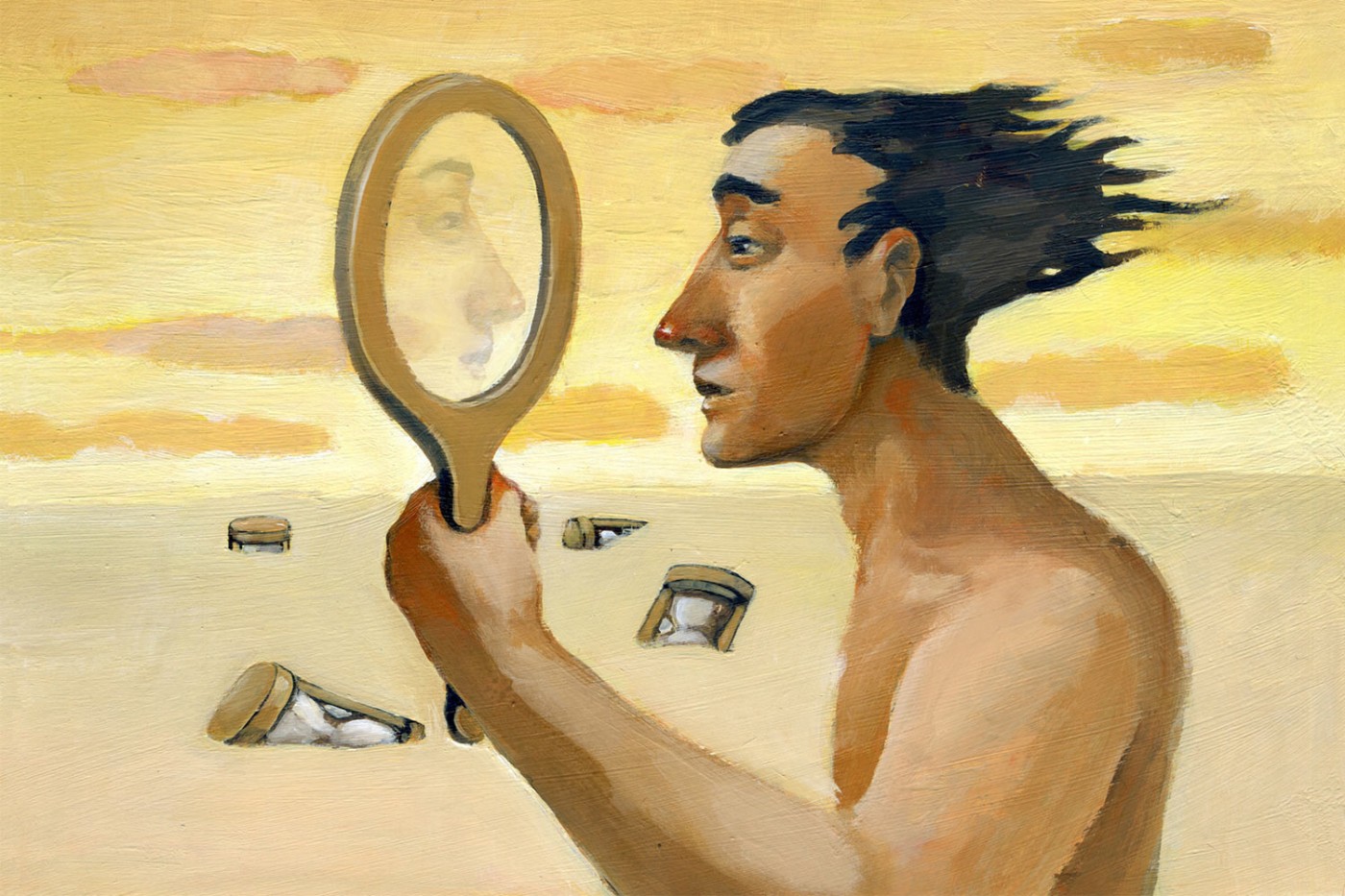

The loss of a socially acknowledged identity and voice is a thought to keep in mind, as we try to imagine and empathise with the first-hand experience of someone diagnosed with dementia. Alzheimer’s disease, the most commonly occurring of the syndrome’s four main types, is primarily marked by profound memory loss that eventually leaves its victim incapacitated, unable not only to perform the simplest of everyday tasks, but also incapable of rallying sufficient memory to form a coherent sense of self.

“Cogito Ergo Sum: I think, therefore I am.”

The artist William Utermohlen was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 1991, at the age of 61. The sudden and impending loss of not only his artistic capabilities but also his “self”—the conscious individual made up of all of Utermohlen’s 61 years of memories and experiences—disintegrating with the disease’s ravaging of his memories and linear-thought ability, spurred Utermohlen to furiously begin painting self-portraits.

In his decline, up till the year 2000 when he was thereafter no longer able to, Utermohlen produced numerous works. The dissolution of skill and coherence recorded in the works over the years, as well as their varying states of completion, speak volumes in giving critical insight into the experience of an Alzheimer’s victim.

Details are lost as lines and strokes become increasingly bold, thick and laboured, even as perspective flattens and shapes distort. Utermohlen’s penetrative and haunting gaze eventually obliterates into a mess of smudges and floating sketches. The increasingly garbled, abstract pieces evidence not only the frustration and fear surrounding the loss of learned skill and ability, but also the painful disintegration of self and the individual beyond recognition.

In his essay, “The Disremembered”, author Charles Leadbeater posits that this troubling loss of a single, coherent individual to the symptoms of dementia can alternatively be considered from a more physical, rather than intellectual philosophical standpoint. Very basically put, we can choose to cherish and bring joy to what remains in the wake of dementia—the physically present loved one in the now, instead of focusing on mourning the loss of the intellectual being we knew previously. Their “failing memories make them different, but… not lesser [or with] fewer rights” [and] their “difference” should not be translated as “difficult”. Because they can no longer easily articulate their needs, or follow instruction, nor follow a linear train of thought or existence, the joy of simple tasks and gestures, done in a stable, consistent and conducive environment can help make theirs, and their caretakers’ days more meaningful and even happy.

World Alzheimer’s Day is every 21st of September. Take the time to learn more about the disease, and raise awareness for its rising prevalence and impact on society at the following site.