The Essential Guide for Investing in a Crisis

We are on the cusp of a full-blown recession as the global economy attempts to deal with a simultaneous demand and supply shock caused by Covid-19. Boeing, a company with a US$55 billion market capitalisation reported a complete drawdown of US$13.8 billion in credit facilities, prompting S&P Ratings to downgrade its credit rating to just two notches above junk. As a result, Boeing’s managers had to seek a government bailout of the company. This could prove to be the canary in the coal mine for what is to come for the numerous companies with a lower credit rating than Boeing.

The pieces are starting to fit together as a picture of gloom forms. George Soros’ theory of reflexivity perhaps sums up how markets will evolve from here where the perceptions of economic fundamentals affect reality, which in turn, impact economic outcomes.

The irony of it all is that this is the time to be a contrarian, to act in a manner that is in direct opposition to the herd. Behavioural finance and psychology predict in no uncertain terms that investors will be net sellers in dire times such as these, when in fact, they should be net buyers. This calls for a fortitudinous and steadfast attitude from investors who want to capitalise on these whirlwinds. Fortune favours the bold; so here are some ideas on maximising returns in a bear market.

Global Investing

Home country bias is a prevalent bias when it comes to investing in today’s markets; where we live, work and play affects our worldview and the decisions we make. Asset managers frequently espouse the tenets of global investing, telling investors why they should avoid familiarity at all cost because they have “emerging market” themes to sell.

But all of these are not without merit. For one, the expected GDP growth in other countries may exceed that of your home country in the coming years. The second reason is that valuations in certain countries are reasonably attractive from the perspective of a value investor.

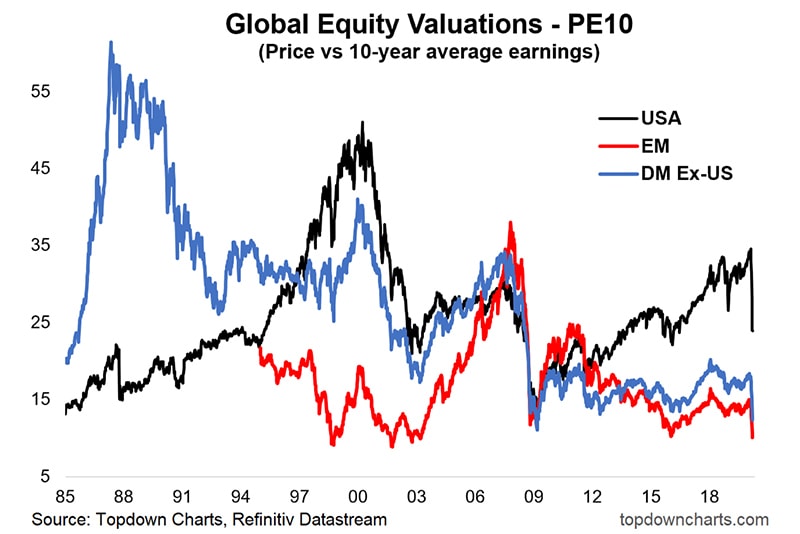

Global investing gives one the opportunity to find extreme bargains in other parts of the world, like well-governed companies with rock bottom valuations. In general, Asia is cheaper than the US and while Singapore is attractively priced at a PE ratio of 12.2, countries such as China have a higher expected return of 29.85% versus Singapore’s 23%.

Valuations and Potential Takeover Targets

The question of when to buy is often answered by asking another question: Are valuations low enough? This must be the modus operandi of investors who seek to profit from a crisis. Investors who believe in the theory of investment value recognise that the summation of all discounted cash flows of an asset’s life will result in the intrinsic value. The idea here is to buy at a discount to the intrinsic value. However, the problem is that the estimated intrinsic value is often subjective. More often than not, estimated growth rates and discount rates differ from reality.

A realistic way of removing subjectivity is to buy at prices way below what a private owner would pay for the entire company—aka the private market value. Mario Gabelli, a fund manager from Gamco Investors Inc., is a proponent of this approach of stock appraisal—and keeps a veritable database of companies with an estimated private market value.

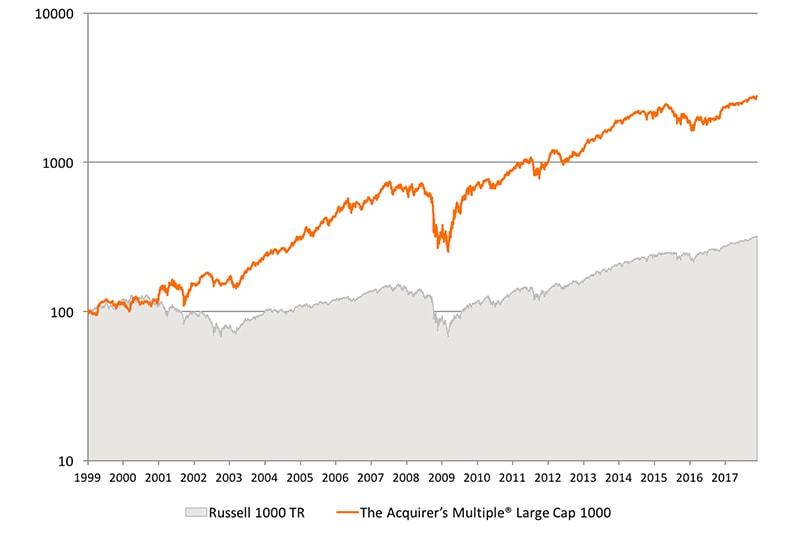

If the private market value sounds too arcane, Tobias Carlisle, a fund manager and author, proposes buying the cheapest companies on a EV/EBIT (Enterprise Value/ Earnings Before Interest & Taxes) or EV/EBITDA (Enterprise Value/Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation & Amortization) basis. According to Carlisle, the cheapest companies represented by the EV/EBIT ratio are practically takeover targets. While I am not entirely convinced of his argument, backtests show that buying the cheapest of such stocks tend to produce returns of around 19.3% from 1999 to 2017. When you look at it through the lens of a statistician, this method of stock picking becomes cogent (see chart below).

Source: Acquirer’s Multiple – Results of backtest of EV/EBIT strategy vs Russell 1000

Source: Acquirer’s Multiple – Results of backtest of EV/EBIT strategy vs Russell 1000

It may be wise to estimate the debt capacity of a company then. If the company trades at less than its comfortable debt capacity, the company becomes a “sitting duck” for private equity firms or other industrialists because an acquirer can utilise the untapped borrowing capacity of such companies to finance a leveraged buyout.

Case in point, CSS Industries Inc, a company selling craft, gift offerings and sewing kits. In 2019, the company turned in a loss. However, the company had been predominantly profitable over the last decade. Granted that it is not the most “sexy” company out there, its average EBITDA/share over 9 years was US$2.55 and quite comfortably, this relatively debt-free company could put US$10 per share of debt on its balance sheet and service it comfortably. When the share price slid to $6, I went in. Not long after, CSS Industries shareholders received an offer of $9.40 from IG Design Group PLC, netting me a 50% return in less than six months.

Debt Considerations

The presence of debt on a company’s balance sheet increases the range of outcomes for a company entering a recession. If it has too much debt, it could affect a company’s survival. If it has too little debt, it may be accused of being capital inefficient. Whatever the case may be, it would make sense for most investors to play safe, and invest in companies with a conservative capital structure. That being said, if you have a bigger risk appetite, you should look at debt servicing abilities and covenants that a company has with its creditors.

Preferably, investors should insist on companies with debt maturities pushed three years out so that it does not get affected by the possibility of a credit crunch in the short term. Such companies with managerial foresight usually have the space to effect changes within the company’s capital structure (to pay down debt).

Examining the debt covenants of a company is also essential. The waiver of debt covenants usually occurs if a company has consistently stable cash flows, and cash generative companies with long operating histories have a higher likelihood of surviving a crisis than others.

The Search for Yield and Law of Averages

For many investors, volatility can be a real stomach-churner, compounded by the global economic uncertainty. It would be nice to have consistent dividend cheques coming through the mail or one’s brokerage account every now and then. Such dividend-paying companies with the prospect for capital appreciation will present themselves during a crisis. On the upside, recessions provide investors with the opportunity to find ample conservatively-financed, dividend-paying companies, paying a dividend yield in excess of a AAA bond. Think of it as bond-like investments.

Companies going through a particularly rough time may choose to suspend dividends temporarily or even cut them. And that allows investors to buy on cheap. Assuming the law of averages proves correct, a company that usually pays dividends will continue to do so in the future.

Regardless of the various opportunities available, it is always good to have income flowing in to ameliorate the effects of a volatile market. After all, wouldn’t it be good to be paid to wait?

There is immense certainty that the markets are heading south. And soon, it will be a stock picker’s haven. Factor-investing models will continue to work and be eight times as predictive during a recession compared to normal times, but do investors have the stomach for it?