In Praise of Walking

“Where does it start? Muscles tense. One leg a pillar, holding the body upright between the earth and sky. The other a pendulum, swinging from behind. Heel touches down. The whole weight of the body rolls forward onto the ball of the foot. The big toe pushes off, and the delicately balanced weight of the body shifts again. The legs reverse position. It starts with a step and then another step and then another that adds up like taps on a drum to a rhythm, the rhythm of walking.”

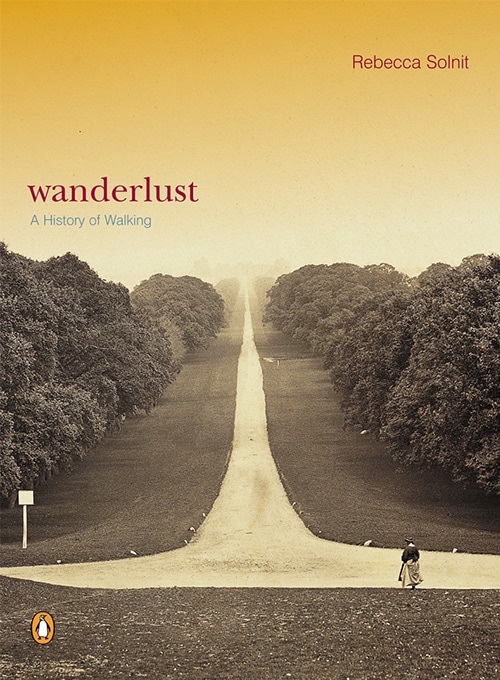

Walking is the most intuitive and mundane physical act in the world, a powerful movement that allows us to discover landscapes, philosophy, history and our identities. In a witty and cogent compendium of three centuries of walking, Rebecca Solnit’s “Wanderlust” investigates the declining phenomenon which has defined humanity for its entire breath—documenting the historical journeys of poets, philosophers and women who fight to roam freely in an age of patriarchy. From William Wordsworth to Gary Snyder, Jane Austen’s Elizabeth Bennet to Andre Breton’s Nadja, Solnit finds a profound relationship between walking, thinking and forming connections.

In Jane Austen’s novels, “Walking provided shared seclusion for crucial conversations”—the 19th century answer to gossiping in style. Later, Wordsworth, who famously estimated to have walked 175,000 miles in his lifetime wrote passionately about his ambles in the Lake District—penning poems such as “An Evening Walk”, and inspiring other poets with his words (and fitness levels). He reckoned the act of sauntering can be closely related to the creative process, using his time on foot to create poetry.

“Wanderlust” fascinates with its colourful narration into the history of walking, but Solnit has a deeper message—reminding us about the importance, beyond its pragmatic function of mobility. Although, as the book suggests that “most of the time walking is merely practical, the unconsidered locomotive means between two sites”, the true value lies in the ability to expand our minds. Walking is also a form of intimacy with oneself—with one’s imagination and thoughts. Many celebrated authors like Jane Austen and Charles Dickens often took walks in parks to gain artistic inspiration, as the practice induces a deeper state of consciousness with ourselves and our surroundings, which Solnit effectively captures in these lines. “Walking, ideally, is a state of mind in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes finally making a chord. Walking allows us to be in our bodies and in the world without our being made busy by them. It leaves us free to think without being lost in our thoughts.” A riverside amble, for example, has the power to discipline the careless meanderings of the mind and to help us organise our thoughts coherently.

These days, the privatisation of walking places and rapid transportation have both reduced walking to obsolescence. Still, Solnit urges readers to see a truth that we are only subconsciously aware of: the less we walk, the further we are distancing ourselves from our bodies and minds. The perilous balancing act of living with presence is a struggle, but one we must learn to cultivate. She writes: “Thinking is generally thought of as doing nothing in a production-oriented culture, and doing nothing is hard to do. It’s best done by disguising it as doing something, and the something closest to doing nothing is walking. Walking itself is the intentional act closest to the unwilled rhythms of the body, to breathing and the beating of the heart. It strikes a delicate balance between working and idling, being and doing. It is a bodily labor that produces nothing but thoughts, experiences, arrivals.” Walking is an activity that connects both the mind and body with the world—and through it, we get to encounter the unexpected, the spontaneous and the hidden.

Solnit further argues for the importance of preserving the space to walk, especially in our highly urbanised world. “Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors—home, car, gym, office, shops—disconnected from each other. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it.” Walking is a bastion against the disintegration of relationships caused by the interminable desire to be more productive. Along with that are imposing metallic structures that dominate our skyline in all their silver glory, serving to separate and imprison us physically and metaphorically. This alienation in our post-industrial world has created a greater need to walk to reclaim the loss of our identities and relationships.

“Wanderlust” is a lively and enchanting read that keeps a quick rhythm with its stories, anecdotes and history. Solnit does make a resounding case that walking is one of life’s biggest pleasures—and is something we mustn’t overlook or take for granted.