Making Sense of Interest Rates Is Common Sense

We have been in the seemingly boring preoccupation of following interest rates and bonds for a quarter century now, so it is a pleasant surprise to see everyone around us start to pay attention to our stuff. Many profess to be Singapore government treasury bill (t-bill) experts these days, while ranting about the extra two thousand dollars they are paying on mortgages each month that happened with little notice in the last two months.

Indeed, nearly every bank except Credit Suisse has published record profits and Singapore banks like DBS are still paying only 0.05 per cent on their regular savings account, which means those record profits are a thing of the past because of glorious government bills and Singapore Savings bonds. 4.19 per cent for six months (based on the last auction result), 100 per cent guaranteed by the Singapore government versus only $75,000 if it is in a bank account that is only paying 0.05 per cent. Unless you decide to perform monkey antics that banks like OCBC are demanding you do before you get “up to 4.65 per cent,” with all the terms, conditions and qualifiers.

We heartily salute those who patiently queued hours to buy t-bills for their CPFIS accounts and congratulate those who managed to lock in their home loans at 1.58 per cent in March for the next two years, or those who locked in three years at 1.3 per cent late last year.

At the same time, we commiserate with those who had borrowed at SORA +1.3 per cent earlier this year, which became SORA +0.75 per cent in July before the latest promotion we saw last week advertising SORA +0.3 per cent home loans.

What a fiasco.

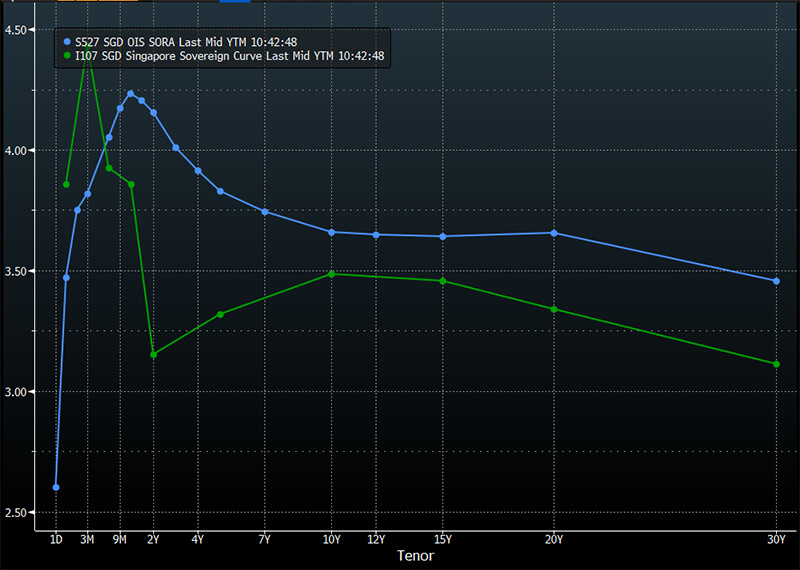

As we said in our previous post, Food for Thought: SORA, Ever the SOR Be?, the SORA index used in housing loans is a backward-looking index and the three-month SORA will only be known after three months. We can see the gap in the graph below where the six-month SORA index is at 1.9 per cent versus the expected rate of over 4 per cent traded in the market.

Kudos to the lucky folks who have those interest-offset mortgage loans that are pegged to SORA for the time being.

Yet for the wisdom of the crowds, banks like UOB have seen their CASA (Current Account Savings Account) ratio drop under 50 per cent, indicating a withdrawal of money—meaning they would have to rely on other sources of funds for their operations.

There is a conspiracy theory that the situation would persist as banks can scarcely let their regular deposit rates rise for it would affect the CPF Ordinary Account rate (2.5 per cent) which is pegged to the HDB housing loan rate (CPF+0.1 per cent). This affects a lot of citizens and has nothing to do with HDB’s record deficit of $4.367 billion incurred in 2021. Come on, 2.45 per cent won’t kill the banks!

No time to rant would be a dear friend of ours, looking ashen and slightly worse for the wear, who spent all her CDC vouchers on cigarettes after a week in the front lines of the bond market.

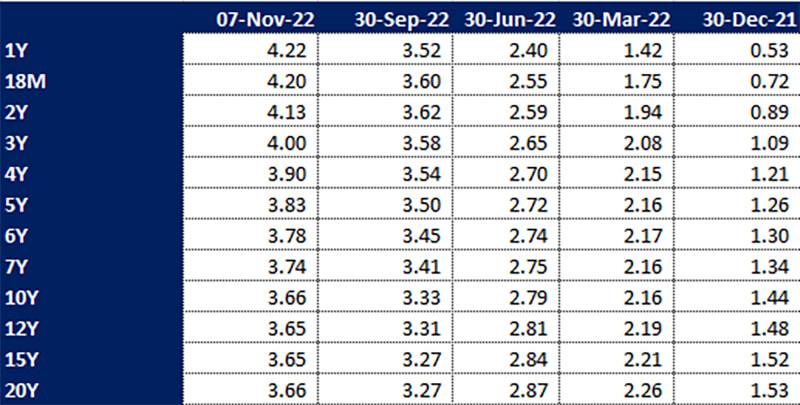

She had ranted earlier about how the 10-year interest rate was holding patriotically around the 3.5 per cent level, to complement the CPF Special Account rate which is much lower than 2-year interest rates.

We have been operating in an inverted rate curve environment for several months now. Refer to the inverted Singapore interest rate swaps and government bond curve below and note how the short-end rates dwarf the longer tenors. We asked our friend how she prices bonds these days.

Her answer was to disrespect the curve! If it doesn’t make sense, use common sense.

For six months ago, as inconceivable as it may look now, the 6-month reference rate was 1.8 per cent. She decided it was untenable and began using 2.5 per cent, changing her reference points along the way. She uses her own model till now; 4.25 per cent as the 10-year rate instead of the 3.6 per cent the market is assuming.

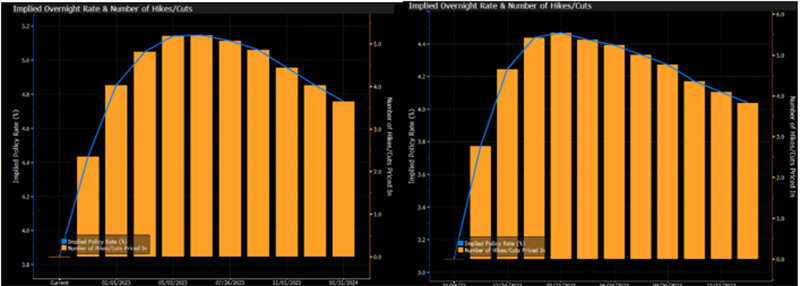

Bond pricing has become an art of sorts and she confessed it is getting impossible as we speak because nobody knows where the terminal rate will be because it was 4.4 per cent last month. Now it is 5.2 per cent when it was just 3.25 per cent a few months ago. Take a look at how market expectations have changed in a month in the graph of the projected Fed funds rate below.

No longer do we use normal assumptions because the reference curves are simply unreliable. The price discovery process is broken like what happened this week in bond markets with callable bonds, which are now starting not to call and redeem their bonds. We had two in Singapore this week along with the high-profile non-calls in South Korea which led to a massive meltdown, decimating many a portfolio as prices tumbled up to 30 per cent in a day.

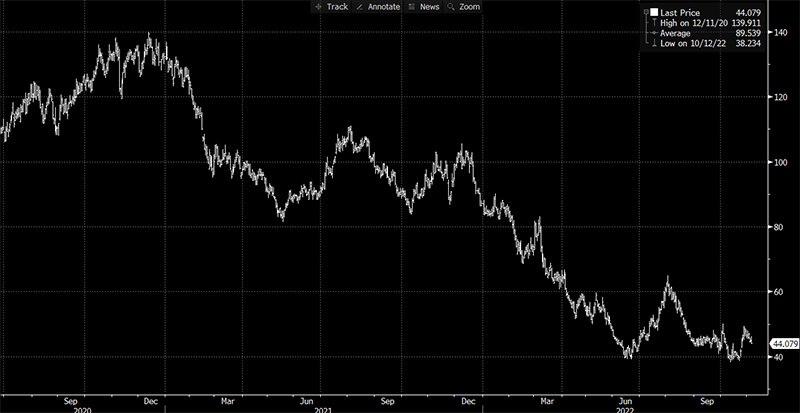

Who is to know when they will ever call if the bond maturity is perpetual? Lucky for her who started assuming 2049 a few weeks ago but now debating if 2071 is a better idea because one of the longest bonds in the world, the Austrian 100-year government paper, once the darling of markets is now trading at 44 cents to the dollar, which gives it an approximate yield of 2.3 per cent. We shudder to think even 4 per cent.

Price chart of the Republic of Austria 0.85% 2120 bond. Source: Bloomberg

Price chart of the Republic of Austria 0.85% 2120 bond. Source: Bloomberg

How can we even think of terminal rates when British banks like HSBC just paid over 7.3 per cent for 4-year senior bonds in US dollar just this week versus the current Fed funds rate of 4 per cent and 3-year US government bonds at 4.59 per cent.

It is poo-poo if they expect her to believe 10-year interest rates in Singapore should be 3.66 today because it closed 2021 at 1.53 per cent (refer to the table below) and woe to those poor buggers who thought bonds were cheap last year because there are less than half dozen bonds in Singapore dollars holding above their issued price.

4.25 per cent is her anchor (for time being) in her new model called “Disrespect the Curve!”

Yet let us use a little common sense here and ask ourselves why should we live in a 5.2 per cent world today when it was 4.4 per cent a month ago and 3.25 per cent recently before that?

It happened so quickly, the pace of increase that folks are getting caught off guard with the extra $2,000 in mortgage payments and all, that even banks are feeling the pinch of borrowing. Imagine the demand destruction for omakase dinners and such that is happening to us (except for those who had locked in those 1.3-1.58 per cent fixed rate loans assuming they have not lost money in their portfolios).

Common sense says that the economic slowdown will be swift and sharp and as economic data is “backward-looking,” the shock will only be known in the months ahead, although it does not imply or guarantee that inflation will go away given rising wages. But it does mean governments and central banks will have a recession on their hands as well as inflation which may sway their outlook for interest rates even if the Fed’s dual mandate is employment and inflation. This week, we had U.K.’s Jeremy Hunt stating he would like “interest rates to be kept as low as possible” after the Bank of England raised interest rates by the largest amount, 0.75 per cent, since 1989.

With all due respect to the market, interest rate volatility is at a crisis, conventional bond-pricing models are failing and we have enough signs of an economic downturn such as the 3-month and 10-year inversion of the US government bond curve. The drop in South Korea’s exports, its worst fall in 2-years, is seen by market watchers to herald a global downturn.

It is a timely reminder, entering the final months of the year and heading into quite an unknown 2023— to use commonsense.