Scale vs. Soul: Is Bigger Always Better?

In late 2018, Thrillist published a bombshell piece titled I Found the Best Burger Place in America. And Then I Killed It. Food writer Kevin Alexander details how he had named a little-known burger joint in Portland the best burger in America, only to learn that the resulting influx of people allegedly caused the place to shut down. In the article, Alexander blames himself for turning Stanich’s from a local joint to a destination restaurant that became overrun and eventually overwhelmed by “burger tourists”. We’ve heard these stories before. The latest one entails Sukiyabashi Jiro (from the 2011 documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi) being dropped from the Michelin guide, because of its explosion in popularity—making it near impossible for the general public to get a table there.

These examples suggest that in our hyperconnected world, “making it big” comes with an inevitable tension between scale and soul. When going viral and economies of scale come into play, they are always framed as positive outcomes. But we talk less about what happens after that, the loss of qualities that made a company big in the first place. The soul which drew people to it like a magnet. In Stanich’s case, staff were inundated and overwhelmed by customers who were there to check off eating the best burger in the U.S. but didn’t know or care for how things were done at Stanich’s. The sheer volume of business, which should have helped the joint thrive, paradoxically destroyed the quality of food and experience that made Stanich’s a phenomenon.

When it was both more costly to travel considerable distances and difficult to obtain comprehensive information about what is out there, local services (eateries, pubs, coffee shops, etc.) thrived and were more important in people’s lives. Our local kopitiam or hawker centre is a cornerstone of the local community because the owners and clientele have developed memories, relationships and even a sense of familiarity over long periods. In a way, these spaces are siloed and cater only to their local community, distinguishing themselves from the hundreds of other such spaces across the country. This uniqueness translates into what we often call the charm or character of a place. And it is the reason why we feel an affinity to it.

These days, local spaces and services are disappearing partly due to how easy it is to compare our options and how accessible these options have become. With a few strokes of the keyboard, we can check the reviews and ratings of any restaurant in the country. With a few taps on our smartphone, we can order dishes from multiple restaurants, or hop into an Uber that will quickly take us to whichever one we’re in the mood for. This ease and convenience have necessitated a mindset shift: Why settle for what’s local when you can go to the “best”? There are countless articles and blog posts reflecting on our obsession with lists and rankings, but these are only symptoms of a more fundamental change in consumption, facilitated by technology.

Naturally, our understanding of what it means to have a good meal is now benchmarked not against our local surroundings, but what lies beyond that—which is your city or country for regular folk, and the whole world if you happen to own a private jet. The cliché about the world becoming smaller with globalisation has a good dose of truth to it. What is accessible to us today was unthinkable just a decade ago, thanks to the Internet and connectivity, which have made global scale and reach possible. This may appear enticing to any business owner, but for Stanich’s and Sukiyabashi Jiro, their popularity turned out to be more detrimental than beneficial.

Research has shown that when products such as books win awards and subsequently reach a larger audience, the ratings of these books ironically decrease. Inevitably, with greater exposure, being subjected to public scrutiny increases along with the number of naysayers and people who simply don’t appreciate what you do.

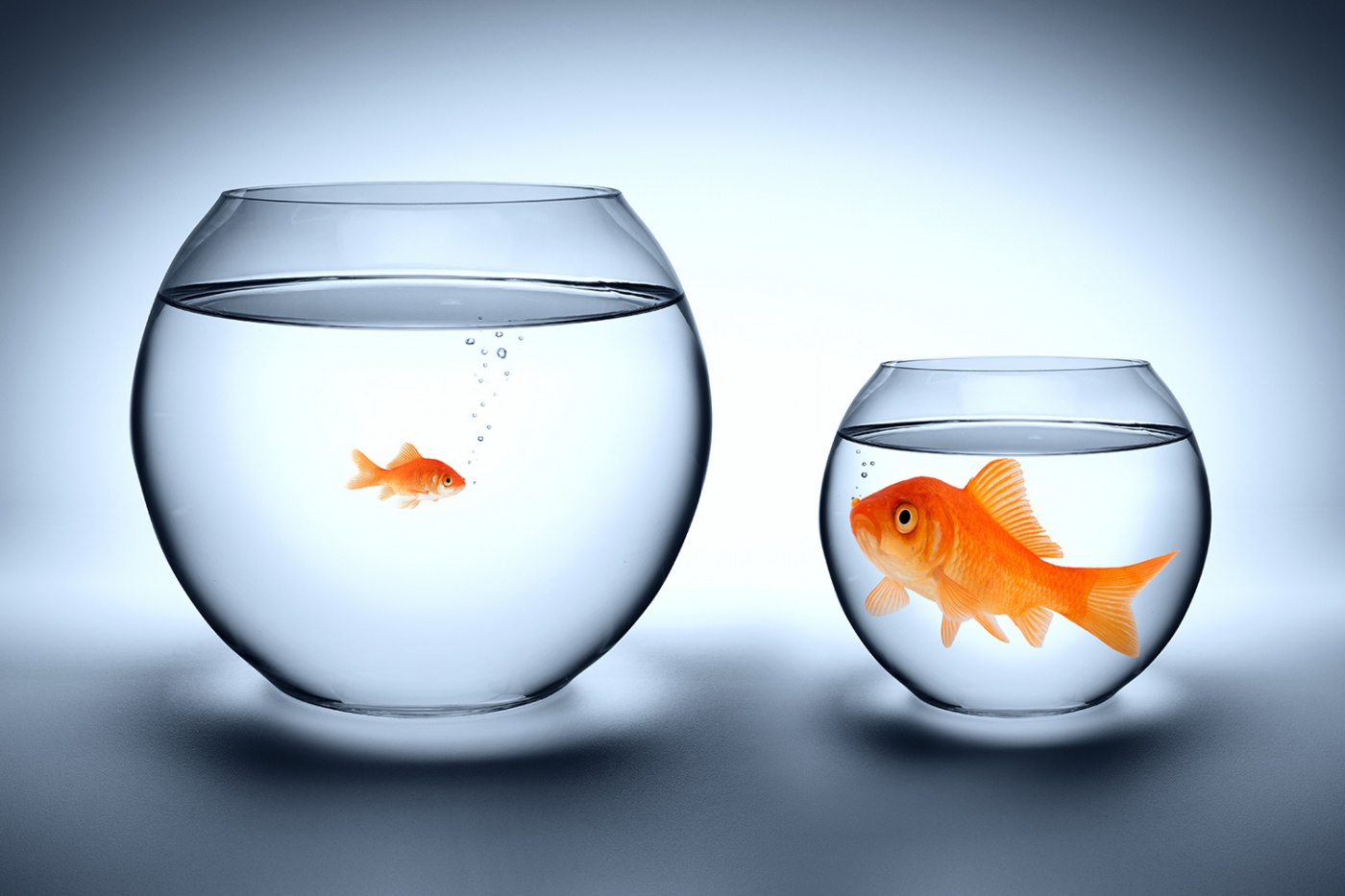

Ultimately, the bigger question is: Do you want to be a big fish in a small pond or a small fish in a big pond? The answer is, of course, a personal one. Obviously, there are pros and cons to scaling and expanding your reach as well as staying “boutique” and true to your roots. Staying in a small pond allows you to build deep connections within a community and make your contributions felt. While grinding it out in large organisations or “making it big” seems glamorous and exciting, the reality of being in that environment often reduces people to feeling like they’re a cog in a machine. At some point, you just have to pick your poison.